Women should be told about their breast density when they have a mammogram

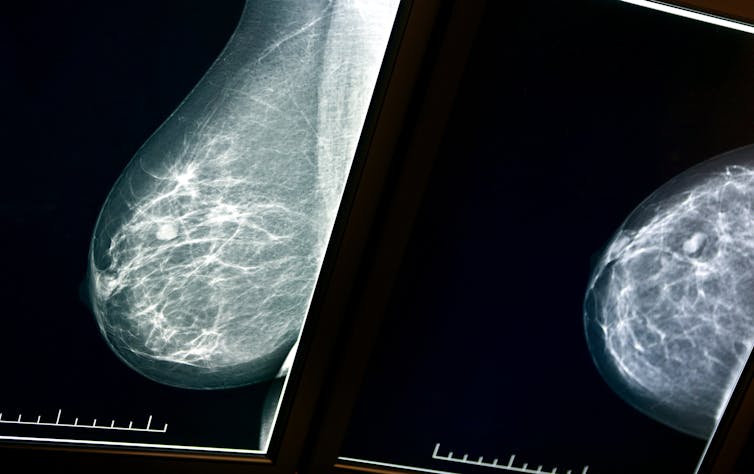

Breast density appears white or bright on mammograms ŌĆō so do breast cancers.

┤Ī│▄│┘│¾┤Ū░∙▓§:╠², ; , ; , ; , ; , ; , , and ,

Women with higher breast density for their age are more likely to develop breast cancer. High breast density also makes it harder for doctors to detect breast cancer on a mammogram. But Australian women are not routinely tested for and told about their level of breast density when they undergo a mammogram.

A womanŌĆÖs breasts are made up of dense breast tissue and fatty breast tissue. Almost have extremely high breast density. This means they have more connective tissue and less fat surrounding their glands.

Breast density canŌĆÖt be determined just from looking at or physically examining the breasts; itŌĆÖs measured from a mammogram, an X-ray of the breast. Breast density appears white or bright, while non-dense breast tissue appears dark.

Breast cancers also appear white on a mammogram. So having high breast density can mask or hide the cancer, making early detection more difficult. This is especially important because women whose breast cancers that are found within 24 months of a ŌĆ£clearŌĆØ mammogram tend to have poorer outcomes.

Across the population, a woman has a 12.5% chance of getting breast cancer in her lifetime. Women who have high breast density for their age and body mass index (BMI) have a risk of developing breast cancer in the future compared to women with low breast density.

We are a group of breast cancer scientists concerned that Australian women are not being made aware of the significance of breast density in the diagnosis and prevention of breast cancer. We want to start a conversation about what density is, even though we donŌĆÖt yet have all the answers.

We would like to see health professionals (including researchers, radiologists, GPs and BreastScreen) begin talking with women about the best way to measure and report breast density.

What can women do about it?

A womanŌĆÖs breast density is established at the time her breasts form, and is largely determined by genetic factors.

ŌĆ£EnvironmentalŌĆØ factors then can modify breast density over time. This includes having children, which reduces breast density, and taking certain hormone therapies: hormone replacement therapy increases density, while the drug decreases density.

Further reading:

We donŌĆÖt yet have a straightforward answer about what women with high breast density for their age should do.

Being ŌĆ£breast awareŌĆØ is important for all women, but particularly women with higher breast density. Get to know how your breasts feel and check them regularly for changes.

Mammography is the best breast cancer screening test for women aged 50-74 who arenŌĆÖt showing any symptoms. Early detection improves the outcomes for women with breast cancer, as therapies are more effective at early stages of disease and chances of survival are increased.

For women aged 40 to 49 and over 75, the research is less clear about the benefits of breast screening.

Supplemental screening options such as ultrasound and MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) are available for women with high breast density. However, these also have a number of limitations and are not covered by Medicare for this purpose.

Ultrasound often results in high rates of false positives, indicating that breast cancer is present when it is not. A false positive can be a distressing experience, with additional tests sometimes being required such as a breast biopsy.

MRI does not lead to higher false positives, but it is not a feasible option for a population-based screening program because of the high costs and insufficient MRI resources (equipment and trained staff).

A further problem is there are few options to reduce breast density once it is detected.

is a drug used to prevent or treat breast cancer that reduces breast density and breast cancer risk. But it has significant side effects such as hot flashes, vaginal dryness, low libido, mood swings and nausea, which need to be considered on a patient-by-patient basis.

In counselling women about their breast cancer risk and screening options, clinicians will also ask about a womenŌĆÖs other breast cancer risk factors, particularly family history of the disease.

What might be available in future?

Researchers and clinicians have been investigating breast density for around 40 years. But there is still a lot we do not know.

The long-term goal of our research ŌĆō in Australia and abroad ŌĆō is a tailored screening program where women undergo good-quality screening measures based on their levels of breast density and their breast cancer risk.

First, we need to determine if women with higher breast density would benefit from supplemental screening mentioned above, or annual mammograms.

Our research teams are currently investigating:

- the underlying biology of breast density to inform the development of new drugs to decrease density

- the optimal methods of measuring breast density across the population and in younger women, for whom mammography is not recommended

- to determine the individual likelihood of developing the disease or having it go undetected

- breast density in

- and the genetic determinants of breast density and breast cancer risk to inform individual risk prediction models.

We donŌĆÖt want to scare women that have higher breast density for their age. Rather, we want to inform them about their risk of breast cancer and the additional care they should take until we find treatments that can reduce density and breast cancer risk. Not all women with high breast density will develop breast cancer, but they should be aware that they are at an increased risk.

![]() For more information on breast density, visit the .

For more information on breast density, visit the .

, Senior Research Fellow at Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre; Adjunct Lecturer, ; , Postdoctoral Research Fellow, ; , Senior Research Fellow, Centre for Genetic Origins of Health and Disease, ; , NHMRC Australia Fellow, ; , Australian Breast Cancer Research Postdoctoral Fellow, The Queen Elizabeth Hospital and The Robinson Institute, ; , Professor of Breast Cancer Research, Institute of Health and Biomedical Innovation and School of Biomedical Sciences,, , and , Associate Professor,

This article was originally published on . Read the .