Water is one of AustraliaÔÇÖs most valuable commodities. Rights to take water from our nationÔÇÖs largest river system, the Murray-Darling Basin, are worth almost A$100 billion. These rights can be bought and sold or leased, with trade exceeding . But water is also being stolen (no-one knows how much) and the thieves usually get away with it.

The federal Labor government came to power promising to in the Murray-Darling Basin. The has also expressed concerns about a lack of compliance and enforcement.

The Inspector General of Water Compliance, Troy Grant, has also described existing , and called for urgent action to address inconsistencies in the various state laws that penalise theft from the Murray-Darling Basin. That was almost a year ago.

In , we identified the many relevant laws operating in the basin. We examined these laws and found maximum penalties range wildly. It is a dogÔÇÖs breakfast. Surely we can do better.

How did we get into this mess?

The mishmash of water theft laws and penalties across the basin is unfortunate but not surprising.

Water in the Murray-Darling Basin is managed under a between the federal government, the basinÔÇÖs four states (Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria and South Australia) and the Australian Capital Territory.

This agreement could be dissolved at any time, should any one state or territory decide to quit.

Murray-Darling Basin compliance is now managed by the Office of the Inspector General of Water Compliance, an independent group of public servants, typically former police officers.

As Inspector General, Grant has been given powers to reduce water theft, uphold compliance with Murray-Darling Basin rules, and restore confidence among those living and working in the basin.

But he was forced to drop 62 cases in February 2023 due to poor state legislative support, inconsistent approaches to water theft, and allowances for some irrigators to balance their accounts in arrears. Basically, you had to be a moron to be caught.

Dropped cases lead to questions about water values, continued supply reliability, the extent of environmental harm, and the future security of water rights.

In New South Wales, the independent regulator spoke to neighbouring farmers about water theft (Natural Resources Access Regulator)

Drought heightens concern about theft

ItÔÇÖs almost 15 years since the of water theft legislation across state and federal boundaries, which highlighted clear inconsistencies in penalties and approaches to cases.

ItÔÇÖs also nearly ten years since the into large-scale water theft, illustrating the dangers of environmental water harms and wanton disregard by some users for the rights of others.

In more recent droughts, such as the ÔÇť, irrigators were more concerned about than theft.

But if the basin suffers another serious drought, as , it is likely theft will become a top concern for all involved, particularly regulators at state and federal levels.

WhatÔÇÖs more, if are right, available water will dramatically decline in the Murray-Darling Basin, possibly motivating more theft.

We tested this by combining rainfall and runoff data from the Bureau of Meteorology with climate projections from the CSIRO Climate Futures Model and the , to generate a model of future water flows into the southern Murray-Darling Basin up to 2100.

shows weÔÇÖre on track for a water runoff catastrophe by around 2060, and the eventual collapse of the riverÔÇÖs systems by around 2080. Less rain and higher evaporation rates means less water will runoff the land into streams, rivers and storages. Sobering stuff.

Finding common ground

Our research shows the Inspector General is right: a base comparison of the laws in each state show clear differences, along with the penalties that sit behind them. Calls for greater certainty and consistency are yet to resonate. The positive lessons to be drawn from successful processes are falling on deaf ears.

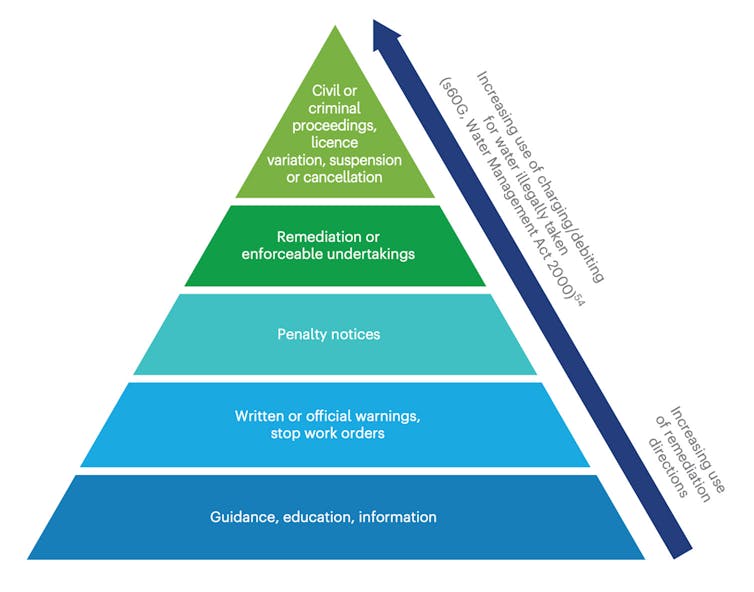

But we did find some consistent aspects worth noting, which could help us better understand and analyse the legal framework for penalising water theft in the Murray-Darling Basin. This is the ÔÇťpyramidÔÇŁ approach to assessing cases and applying penalties, using a tiered framework of increasing severity that looks to be applied universally throughout the basin.

The pyramids are based on already in use for water management around the world.

Most Murray-Darling Basin states already follow this approach. Yet some states do it better than others.

The independent regulator in NSW uses the pyramid approach, where increasing impacts of non-compliance result in more severe responses as you move up the ÔÇśenforcement pyramidÔÇÖ Author supplied

Legal inconsistency also stems from some states being unwilling to ÔÇťclimb to the topÔÇŁ of the pyramid and initiate court proceedings against the most egregious offenders. This leads to lower penalties in most cases.

We also note New South Wales has adopted satellite technology to identify and track water theft. This is a good example for others to follow.

Towards consistent laws

Consistency in compliance and certainty across state jurisdictions will help restore confidence in the water market, and ultimately ensure the Murray-DarlingÔÇÖs water flows are protected from thieves.

We need for water theft across the Murray-Darling Basin and Australia as a whole. Such penalties may garner a wider appreciation of the value of the environment.

Addressing water theft issues consistently and with certainty offers opportunities for Australia to again lead the way in effective water governance and compliance reform globally.

But progress has been slow. This is deeply concerning, especially as water flows into the basin will dwindle as the climate changes.![]()