How algae conquered the world â and other epic stories hidden in the rocks of the Flinders Ranges

Earth was not always so hospitable. Evidence of how it came to be so beautiful and nurturing is locked in the rocks of South Australiaâs Flinders Ranges â a site now vying forÌı.

°¿³Ü°ùÌıÌıÌıseeks to better understand this near billion-year-old story. We discovered immense planetary upheaval recorded in the ranges.

In two related research projects, weâve mapped how the continent that later became Australia responded to the most extreme climate change known in Earthâs history. We then dated this event.

The changes gave rise toÌı. Their legacy is the oxygen we breathe and theÌıÌımore than 500 million years ago. The soft bodies of these animals have been exceptionally preserved at the newÌı, which opened in April 2023.

A superbasin on the shores of the Pacific

The rocks of the Flinders Ranges formed at the same time as the Pacific Ocean basin. The plate tectonic ââ tore North America away from Australia 800 million years ago. This created a valley that became an ocean where sand and mud was deposited.

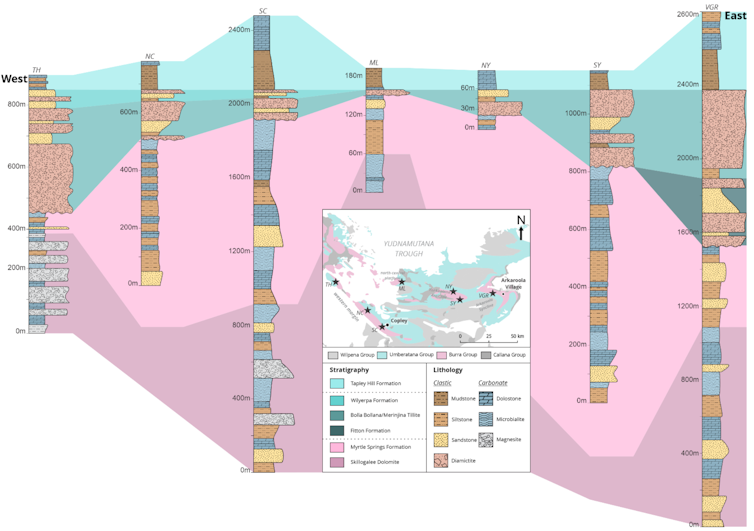

Geologists call this theÌı. âSuperâ because it is huge, and âbasinâ because it formed a depression where sediment could accumulate.

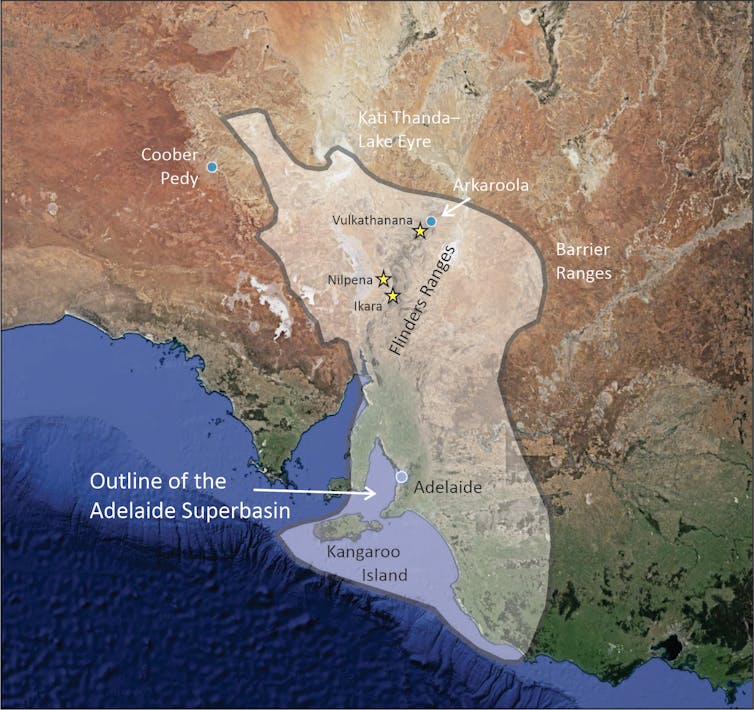

The superbasin stretches from Kangaroo Island in the south, to north of the Flinders Ranges and from Coober Pedy in the west to the Barrier Ranges of New South Wales in the east.

Ìı

At special places such asÌıÌıand the national parks ofÌıÌıandÌı, rocks of the Adelaide Superbasin tell us how our planet came to be the way it is today.

Land of fire and ice

Until about 800 million years ago, Earth was an oxygen-poor but stable planet. So stable, in fact, this time has been nicknamed the ââ.

That all changed 716 million years ago. The planet plunged into an 80-million-year Ice Age, the likes of which has never been seen again. Itâs known as theÌıÌıPeriod.

The Cryogenian contains a least two global glaciations when the planet became covered in ice - an occurrence earth scientists refer to as âSnowball Earthâ. What caused this incredible cooling is still a mystery. But many researchers think it relates toÌıÌıthat directly preceded the icy conditions. The heavily worn remains of these volcanoes haveÌıÌıin Arctic Canada and Alaska.

We know lava from volcanoes reacts with COâ, dragging it out of the atmosphere. Scientists believe this reversed the pre-historic greenhouse effect and theÌı.

Part One: Picturing the world before the first animals

The first part of ourÌıÌıreconstructs the shores of the balmy Pacific as this climate shock hit, causing vast ice sheets to lumber north and smother the region for millions of years.

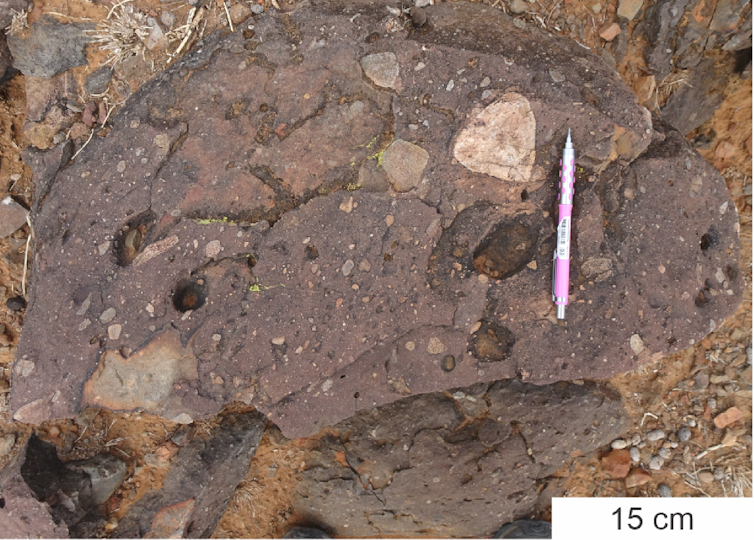

The glaciers ploughed through hills and valleys, planing off the country and leaving behind vast swathes of boulder clay that now forms rocks over much of the Flinders Ranges.

Ìı

Our research analysed unusual magnesium-rich sedimentary rocks in part formed by microscopic bacteria. Hundreds of millions of years later, small variations in the concentration of critical elements are still preserved. We used these variations to build a picture of highly saline shallow seas rich in bacterial life, but devoid of much else.

Part Two: Dating Snowball Earth

Dating sedimentary rocks is challenging. The grains of sand and pebbles that make up the rock formed elsewhere. They were carried by wind or water to the beach, or river, where they were deposited. Then, gradually, new rock formed.

Using established methods we can date one of the minerals in the sand (zircon). ThisÌıÌıgives us the oldest possible age for sedimentary rock. Thatâs a reliable maximum age, but the true age of the rock could be much younger.

In the second part of ourÌıÌıwe combined this established method with a new technique called ââ. This enabled us to more accurately date the Snowball Earth rocks in the Flinders Ranges called the Sturt Formation.

The new technique attempts to directly date the âglueâ that holds the grains of sedimentary rocks together. So weâre using a laser to date minerals that form as the sediment turns to rock. Some of these âauthigenicâ minerals (minerals that form âin placeâ) contain tiny amounts of radioactive rubidium. Over time, rubidium changes to strontium by radioactive decay.

Our study dates mudrock deposited within the glaciation. It is the first study to directly date sedimentary rocks that formed during the Snowball Earth event. This mudrock (a part of the Sturt Formation) formed around 684 million years ago.

Our âdetrital zirconâ method also gave us maximum ages of about 698 million years for a boulder clay below the mudrock, and about 663 million years from a boulder clay above the mudrock. These dates fit with estimates from elsewhere on the globe, suggesting the icy time likely lasted 50 million years.

Put together, the results of these two projects suggest the âSturtianâ glaciation took place between 716 and 663 million years ago and may have been more dynamic than previously thought. Itâs likely there were at least two ice-advance and ice-retreat events, or two separate glacial times. So the planet experienced more of a cold period rather than a completely frigid snowball.

The rise of the algae

These two research projects using rocks within the proposed World Heritage area, along with work from many other researchers, develops a picture of the world that led to the evolution of the first animals. The geological processes and their timing helps us understand how the Earth system came to be.

The frozen world of the Cryogenian stressed the microbial life that dominated the oceans way back then. Glaciers ground rock to powder and this powder turned the oceans of the day to a nutrient soup.

So when warmer times came, a previously minor player in the biosphere bloomed. This newcomer wasÌı, life with cells containing a nucleus. Essentially, seaweed.

They were larger than the life that existed before and better at photosynthesising. They pumped their oxygen waste into the oceans and atmosphere, inadvertently providing the fuel for microbes to combine to form more complex multicellular life forms (metazoans) and ultimately, the first animals.

A place of true world heritage

The rocks of the Flinders Ranges preserve so many stories, from theÌı, to the scars of the early mining history.

Our research into these rocks links the interdependence of Earth systems. Here we find stories about how plate tectonics and volcanoes control the climate, how the climate helps feed life with nutrients and how the resulting life changes the chemistry of the ocean and atmosphere, feeding back into powering new forms of life.

The stories locked in the hills of the Flinders Ranges undoubtedly give the region a heritage value to the world. We eagerly await news of world heritage listing, which isÌıÌıat the earliest.

.

This article is republished fromÌıÌıunder a Creative Commons licence. Read theÌı.

Newsletter & social media

Join us for a sensational mix of news, events and research at the Environment Institute. Find out aboutÌınew initiatives andÌıshare with your friends what's happening.

ÌıÌıÌı